Israelites Came To Ancient Japan

Israelites Came To Ancient Japan

Israelites Came To Ancient Japan

Israelites Came To Ancient Japan

Many of the traditional ceremonies in Japan seem to indicate that the Lost Tribes of Israel came to ancient Japan.

Ark of the covenant of Israel

(left) and "Omikoshi" ark of Japan (right)

Dear friends in the world,

I am a Japanese Christian writer living in Japan. As I study the Bible, I began

to realize that many traditional customs and ceremonies in Japan are very similar

to the ones of ancient Israel. I considered that perhaps these rituals came

from the religion and customs of the Jews and the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel

who might have come to ancient Japan.

The following sections are concerned with those Japanese traditions

which possibly originated from the ancient Israelites.

The reason why I

exhibit these on the internet is to enable anyone interested in this subject,

especially Jewish friends to become more interested, research it for yourself,

and share your findings.

The ancient kingdom of Israel, which

consisted of 12 tribes, was in 933 B.C.E. divided into the southern kingdom of

Judah and the northern kingdom of Israel. The 10 tribes out of 12 belonged to

the northern kingdom and the rest to the southern kingdom. The descendants from

the southern kingdom are called Jews. The people of the northern kingdom were

exiled to Assyria in 722 B.C.E. and did not come back to Israel. They are called

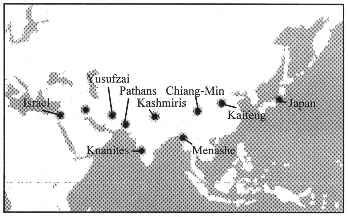

"the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel." The following peoples are thought by Jewish

scholars to be the descendants from the Ten Lost Tribes of

Israel.

Yusufzai

They live in Afghanistan. Yusufzai means children of

Joseph. They have customs of ancient Israelites.

Pathans

They live in

Afghanistan and Pakistan. They have the customs of circumcision on the 8th day,

fringes of robe, Sabbath, Kashrut, Tefilin, etc.

Kashmiri people

In

Kashmir they have the same land names as were in the ancient northern kingdom of

Israel. They have the feast of Passover and the legend that they came from

Israel.

Knanites

In India there are people called Knanites, which

means people of Canaan. They speak Aramaic and use the Aramaic Bible.

Menashe tribe

In Myanmar (Burma) and India live Menashe tribe.

Menashe is Manasseh, and the Menashe tribe is said to be the descendants from

the tribe of Manasseh, one of the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel. They have ancient

Israeli customs.

Chiang-Min tribe

They live in China and have ancient

Israeli customs. They believe in one God and have oral tradition that they came

from far west. They say that their ancestor had 12 sons. They have customs of

Passover, purification, levirate marriage, etc. as ancient Israelites.

Kaifeng, China

It is known that there had been a large Jewish

community since the time of B.C.E..

Japan

This I am going to discuss

about on this website.

In Nagano prefecture, Japan, there is

a large Shinto shrine named "Suwa-Taisha" (Shinto is the national traditional

religion peculiar to Japan.)

At Suwa-Taisha, the traditional festival called

"Ontohsai" is held on April 15 every year (When the Japanese used the lunar

calendar it was March-April). This festival illustrates the story of Isaac in

chapter 22 of Genesis in the Bible - when Abraham was about to sacrifice his own

son, Isaac. The "Ontohsai" festival, held since ancient days, is judged to be

the most important festival of "Suwa-Taisha."

The "Suwa-Taisha"

shrine

At the back of the shrine

"Suwa-Taisha," there is a mountain called Mt. Moriya ("Moriya-san" in Japanese).

The people from the Suwa area call the god of Mt. Moriya "Moriya no kami," which

means, the "god of Moriya." This shrine is built to worship the "god of

Moriya."

At the festival, a boy is tied up by a rope to a wooden pillar, and

placed on a bamboo carpet. A Shinto priest comes to him preparing a knife, and

he cuts a part of the top of the wooden pillar, but then a messenger (another

priest) comes there, and the boy is released. This is reminiscent of the

Biblical story in which Isaac was released after an angel came to

Abraham.

The knife and sword used in the

"Ontohsai" festival

At this festival, animal sacrifices

are also offered. 75 deer are sacrificed, but among them it is believed that

there is a deer with its ear split. The deer is considered to be the one God

prepared. It could have had some connection with the ram that God prepared and

was sacrificed after Isaac was released. Since the ram was caught in the thicket

by the horns, the ear might have been split.

In ancient time of Japan there were no sheep and it might be the reason why

they used deer (deer is Kosher). Even in historic times, people thought that

this custom of deer sacrifice was strange, because animal sacrifice is not a

Shinto tradition.

My friend went

to Israel and saw a Passover festival on Mt. Gerizim in Samaria. He asked a

Samaritan priest how many rams were offered. The priest answered that they used

to offer 75. This may have a connection with the 75 deer which were offered at

Suwa-Taisha shrine in Japan.

A deer with its ears

split

People call this festival "the

festival for Misakuchi-god". "Misakuchi" might be "mi-isaku-chi." "Mi" means

"great," "isaku" is most likely Isaac (the Hebrew word "Yitzhak"), and "chi" is

something for the end of the word. It seems that the people of Suwa made Isaac a

god, probably by the influence of idol worshipers.

Today, this custom of the

boy about to be sacrificed and then released, is no longer practiced, but we can

still see the custom of the wooden pillar called "oniye-basira," which means,

"sacrifice-pillar."

The "oniye-bashira" on which

the boy is supposed to be tied up

Currently, people use stuffed animals

instead of performing a real animal sacrifice. Tying a boy along with animal

sacrifice was regarded as savage by people of the Meiji-era (about 100 years

ago), and those customs were discontinued. However, the festival itself still

remains.

The custom of the boy had been maintained until the beginning of

Meiji era. Masumi Sugae, who was a Japanese scholar and a travel writer in the

Edo era (about 200 years ago), wrote a record of his travels and noted what he

saw at Suwa. The record shows the details of "Ontohsai." It tells that the

custom of the boy about to be sacrificed and his ultimate release, as well as

animal sacrifices that existed those days. His records are kept at the museum

near Suwa-Taisha.

The festival of "Ontohsai" has been maintained by the

Moriya family ever since ancient times. The Moriya family think of

"Moriya-no-kami" (god of Moriya) as their ancestor's god. They also consider

"Mt. Moriya" as their holy place. The name, "Moriya," could have come from

"Moriah" (the Hebrew word "Moriyyah") of Genesis 22:2, that is today's Temple

Mount of Jerusalem. Among Jews, God of Moriah means the one true God whom the

Bible teaches.

The Moriya family have been hosting the festival for 78

generations. And the curator of the museum said to me that the faith in the god

of Moriya had existed among the people since the time of B.C.E.. Apparently,

no other country but Japan has a festival illustrating the biblical story of

Abraham and Isaac. This tradition appears to provide strong evidence that the

ancient Israelites came to ancient Japan.

The crest of the Imperial House of Japan is a round mark in the shape of a flower with 16 petals. The current shape appears as a chrysanthemum (mum), but scholars say that in ancient times, it appeared similar to a sunflower. The sunflower appearance is the same as the mark at Herod's gate in Jerusalem. The crest at Herod's gate also has 16 petals. This crest of the Imperial House of Japan has existed since very ancient times. The same mark as the one at Herod's gate is found on the relics of Jerusalem from the times of the Second Temple, and also on Assyrian relics from the times of B.C.E..

The mark on Herod's gate at

Jerusalem (left) and the crest of the Imperial House of Japan (right)

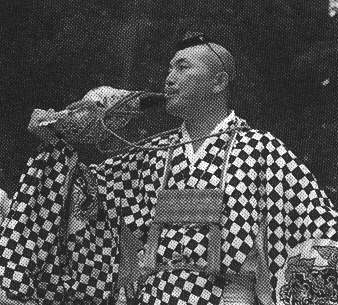

"Yamabushi" is a religious man in

training unique to Japan. Today, they are thought to belong to Japanese

Buddhism. However, Buddhism in China, Korea and India have no such custom. The

custom of "yamabushi" existed in Japan before Buddhism was imported into Japan

in the seventh century.

On the forehead of "Yamabushi," he puts a black small

box called a "tokin", which is tied to his head with a black cord. He greatly

resembles a Jew putting on a phylactery (black box) on his forehead with a black

cord. The size of this black box "tokin" is almost the same as the Jewish

phylactery, but its shape is round and flower-like.

A "yamabushi" with a "tokin"

blowing a horn

Originally the Jewish phylactery placed on the forehead seems to have come from the forehead "plate" put on the high priest Aaron with a cord (Exodus 28:36-38). It was about 4 centimeters (1.6 inches) in size according to folklore, and some scholars maintain that it was flower-shaped. If so, it was very similar to the shape of the Japanese "tokin" worn by the "yamabushi".

A Jew with a phylactery blowing

a shofar

Israel and Japan are the only two

countries that in the world I know of that use of the black forehead box for

religious purpose.

Furthermore, the "yamabushi" use a big seashell as a horn.

This is very similar to Jews blowing a shofar or ram's horn. The way it is blown

and the sounds of the "yamabushi's" horn are very similar to those of a shofar.

Because there are no sheep in Japan, the "yamabushi" had to use seashell horns

instead of rams' horns. "Yamabushis" are people who regard mountains as their

holy places for religious training. The Israelites also regarded mountains as

their holy places. The Ten Commandments of the Torah were given on Mt. Sinai.

Jerusalem is a city on a mountain. Jesus (Yeshua) used to climb up the mountain

to pray. His apparent transfiguration also occurred on a mountain.

In

Japan, there is the legend of "Tengu" who lives on a mountain and has the figure

of a "yamabushi". He has a pronounced nose and supernatural capabilities. A

"ninja", who was an agent or spy in the old days, while working for his lord,

goes to "Tengu" at the mountain to get from him supernatural abilities. "Tengu"

gives him a "tora-no-maki" (a scroll of the "tora") after giving him additional

powers. This "scroll of the tora" is regarded as a very important book which is

helpful for any crisis. Japanese use this word sometimes in their current

lives.

There is no knowledge that a real scroll of a Jewish Torah was ever

found in a Japanese historical site. However, it appears this "scroll of the

tora" is a derivation of the Jewish Torah.

In the Bible, in First Chronicles,

chapter 15, it is written that David brought up the ark of the covenant of the

Lord into Jerusalem.

"David and the elders of Israel and the commanders

of units of a thousand went to bring up the ark of the covenant of the LORD from

the house of Obed-Edom, with rejoicing. ...Now David was clothed in a robe of

fine linen, as were all the Levites who were carrying the ark, and as were the

singers, and Kenaniah, who was in charge of the singing of the choirs. David

also wore a linen ephod. So all Israel brought up the ark of the covenant of the

LORD with shouts, with the sounding of rams' horns and trumpets, and of cymbals,

and the playing of lyres and harps." (15:25-28)

When I read these passages, I think; "How well does this look like the scene of Japanese people carrying our 'omikoshi' during festivals? The shape of the Japanese 'Omikoshi' appears similar to the ark of the covenant. Japanese sing and dance in front of it with shouts, and to the sounds of musical instruments. These are quite similar to the customs of ancient Israel."

Japanese "Omikoshi"

ark

Japanese carry the "omikoshi" on

their shoulders with poles - usually two poles. So did the ancient

Israelites:

"The Levites carried the ark of God with poles on their

shoulders, as Moses had commanded in accordance with the word of the LORD." (1

Chronicles 15:15)

The Israeli ark of the covenant had two poles (Exodus

25:10-15). Some restored models of the ark as it was imagined to be have used

two poles on the upper parts of the ark. But the Bible says those poles were to

be fastened to the ark by the four rings "on its four feet" (Exodus 25:12).

Hence, the poles must have been attached on the bottom of the ark. This is

similar to the Japanese "omikoshi."

The Israeli ark had two statues of gold cherubim on its top. Cherubim are a

type of angel, heavenly being having wings like birds. Japanese "omikoshi" also

have on its top the gold bird called "Ho-oh" which is an imaginary bird and

a mysterious heavenly being.

The

entire Israeli ark was overlaid with gold. Japanese "omikoshi" are also overlaid

partly and sometimes entirely with gold. The size of an "omikoshi" is almost the

same as the Israeli ark. Japanese "omikoshi" could be a remnant of the ark of

ancient Israel.

King David and people of Israel sang and danced

to the sounds of musical instruments in front of the ark. We Japanese sing and

dance to the sounds of musical instruments in front of "omikoshi" as well.

Several years ago, I saw an American-made movie titled "King David" which

was a faithful story of the life of King David. In the movie, David was seen

dancing in front of the ark while it was being carried into Jerusalem. I

thought: "If the scenery of Jerusalem were replaced by Japanese scenery, this

scene would be just the same as what can be observed in Japanese festivals." The

atmosphere of the music also resembles the Japanese style. David's dancing

appears similar to Japanese traditional dancing.

At the Shinto shrine

festival of "Gion-jinja" in Kyoto, men carry "omikoshi," then enter a river, and

cross it. I can't help but think this originates from the memory of the Ancient

Israelites carrying the ark as they crossed the Jordan river after their exodus

from Egypt.

In a Japanese island of the Inland Sea of Seto, the men

selected as the carriers of the "omikoshi" stay together at a house for one week

before they would carry the "omikoshi." This is to prevent profaning themselves.

Furthermore on the day before they carry "omikoshi," the men bathe in seawater

to sanctify themselves. This is similar to an ancient Israelite custom: "So

the priests and the Levites sanctified themselves to bring up the ark of the

Lord God of Israel." (1 Chronicles 15:14)

The Bible says that after the

ark entered Jerusalem and the march was finished, "David distributed to everyone

of Israel, both man and woman, to everyone a loaf of bread, a piece of meat, and

a cake of raisins" (1 Chronicles 16:3). This is similar to a Japanese custom.

Sweets are distributed to everyone after a Japanese festival. It was a delight

during my childhood.

The Bible says that when David

brought up the ark into Jerusalem, "David was clothed in a robe of fine linen"

(1 Chronicles 15:27). The same was true for the priests and choirs. In the

Japanese Bible, this verse is translated into "robe of white linen." In

ancient Israel, although the high priest wore a colorful robe, ordinary priests

wore simple white linen. Priests wore white clothes at holy events.

Japanese

priests also wear white robes at holy events. In Ise-jingu, one of the oldest

Japanese shrines, all of the priests wear white robes. And in many Japanese

Shinto shrines, especially traditional ones, the people wear white robes when

they carry the "omikoshi" just like the Israelites did.

Buddhist priests wear

luxurious colorful robes. However, in the Japanese Shinto religion, white is

regarded as the holiest color.

The Emperor of Japan, just after he finishes the ceremony of his accession to

the throne, appears alone in front of the Shinto god. When he arrives there,

he wears a pure white robe covering his entire body except that his feet are

naked. This is similar to the action of Moses and Joshua who removed their sandals

in front of God to be in bare feet (Exodus 3:5, Joshua 5:15).

Marvin Tokayer, a rabbi who lived in Japan for 10

years, wrote in his book: "The linen robes which Japanese Shinto priests wear

have the same figure as the white linen robes of the ancient priests of Israel.

"

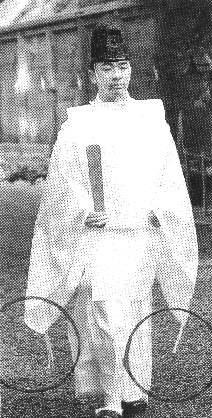

Japanese Shinto priest in white

robe with fringes

The Japanese Shinto priest robe has

cords of 20-30 centimeters long (about 10 inches) hung from the corners of the

robe. These fringes are similar to those of the ancient Israelites. Deuteronomy

22:12 says: "make them fringes in the... corners of their garments throughout

their generations." Fringes (tassels) were a token that a person was an Israelite.

In the gospels of the New Testament, it is also written that the Pharisees "make

their tassels on their garments long" (Matthew 23:5). A woman who had been suffering

from a hemorrhage came to Jesus (Yeshua) and touched the "tassel on His coat"

(Matthew 9:20, The New Testament: A Translation in the Language of the People,

translated by Charles B. Williams).

Imagined pictures

of ancient Israeli clothing sometimes do not have fringes. But their robes

actually had fringes. The Jewish Tallit (prayer shawl), which the Jews put on

when they pray, has fringes in the corners according to

tradition.

Japanese Shinto priests wear on their robe a rectangle of

cloth from their shoulders to thighs. This is the same as the ephod worn by

David: "David also wore a linen ephod." (1 Chronicles 15:27) Although the

ephod of the high priest was colorful with jewels, the ordinary priests under

him wore the ephods of simple white linen cloth (1 Samuel 22:18). Rabbi Tokayer

states that the rectangle of cloth on the robe of Japanese Shinto priest looks

very similar to the ephod of the Kohen, the Jewish priest.

The Japanese

Shinto priest puts a cap on his head just like Israeli priest did (Exodus

29:40). The Japanese priest also puts a sash on his waist. So did the Israeli

priest. The clothing of Japanese Shinto priests appears to be similar to the

clothing used by ancient Israelites.

The Jews wave a sheaf of their first fruits of grain seven weeks before Shavuot (Pentecost, Leviticus 23:10-11), They also wave a sheaf of plants at Sukkot (the Feast of Booths, Leviticus 23:40). This has been a tradition since the time of Moses. Ancient Israeli priests also waved a plant branch when he sanctifies someone. David said, "Purge me with hyssop, and I shall be clean" [Psalm 51:7(9)]. This is also a traditional Japanese custom.

Shinto priest waving for

sanctification

When a Japanese priest sanctifies

someone or something, he waves a tree branch. Or he waves a "harainusa," which

is made of a stick and white papers and looks like a plant. Today's "harainusa"

is simplified and made of white papers that are folded in a zig-zag pattern like

small lightning bolts, but in old days it was a plant branch or cereals.

A

Japanese Christian woman acquaintance of mine used to think of this "harainusa"

as merely a pagan custom. But she later went to the U.S.A. and had an

opportunity to attend a Sukkot ceremony. When she saw the Jewish waving of the

sheaf of the harvest, she shouted in her heart, "Oh, this is the same as a

Japanese priest does! Here lies the home for the Japanese."

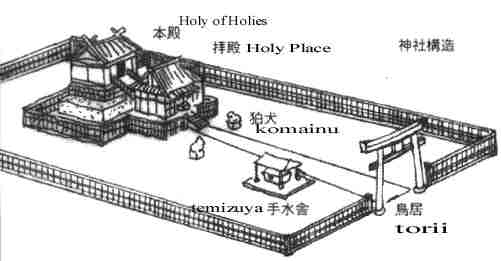

The inside of God's tabernacle in

ancient Israel was divided into two parts. The first was the Holy Place, and the

second was the Holy of Holies. The Japanese Shinto shrine is also divided into

two parts.The functions performed in the Japanese shrine are similar to

those of the Israeli tabernacle. Japanese pray in front of its Holy Place. They

cannot enter inside. Only Shinto priests and special ones can enter. Shinto

priest enters the Holy of Holies of the Japanese shrine only at special times.

This is similar to the Israeli tabernacle.

The Japanese Holy of Holies is

located usually in far west or far north of the shrine. The Israeli Holy of

Holies was located in far west of the temple. Shinto's Holy of Holies is also

located on a higher level than the Holy Place, and between them are steps.

Scholars state that, in the Israeli temple built by Solomon, the Holy of Holies

was on an elevated level as well, and between them there were steps of about 2.7

meters (9 feet) in width.

Typical Japanese Shinto

shrine

In front of a Japanese shrine, there are two statues of lions known as "komainu" that sit on both sides of the approach. They are not idols but guards for the shrine. This was also a custom of ancient Israel. In God's temple in Israel and in the palace of Solomon, there were statues or relieves of lions (1 Kings 7:36, 10:19).

"Komainu" guards for

shrine

In the early history of Japan, there

were absolutely no lions. But the statues of lions have been placed in Japanese

shrines since ancient times. It has been proven by scholars that statues of

lions located in front of Japanese shrines originated from the Middle

East.

Located near the entrance of a Japanese shrine is a "temizuya" - a

place for worshipers to wash their hands and mouth. They used to wash their

feet, too, in old days. This is a similar custom as is found in Jewish

synagogues. The ancient tabernacle and temple of Israel also had a laver for

washing hands and feet near the entrances.

In front of a Japanese shrine,

there is a gate called the "torii." The type gate does not exist in China or in

Korea, it is peculiar to Japan. The "torii" gate consists of two vertical

pillars and a bar connecting the upper parts. But the oldest form consists of

only two vertical pillars and a rope connecting the upper parts. When a Shinto

priest bows to the gate, he bows to the two pillars separately. It is assumed

that the "torii" gate was originally constructed of only two pillars.

In the Israeli temple, there were two

pillars used as a gate (1 Kings 7:21). And in Aramaic language which ancient

Israelites used, the word for gate was "taraa." This word might have changed

slightly and become the Japanese "torii".

Some "toriis," especially of old

shrines, are painted red. I can't help but think this is a picture of the two

door posts and the lintel on which the blood of the lamb was put the night

before the exodus from Egypt.

In the Japanese Shinto religion, there is a

custom to surround a holy place with a rope called the "shimenawa," which has

slips of white papers inserted along the bottom edge of the rope. The

"shimenawa" rope is set as the boundary. The Bible says that when Moses was

given God's Ten Commandments on Mt. Sinai, he "set bounds" (Exodus 19:12) around

it for the Israelites not to approach. Although the nature of these "bounds" is

not known, ropes might have been used. The Japanese "shimenawa" rope might then

be a custom that originates from the time of Moses. The zig-zag pattern of white

papers inserted along the rope reminds me of the thunders at Mt.

Sinai.

The major difference between a Japanese Shinto shrine and the

ancient Israeli temple is that the shrine does not have the burning altar for

animal sacrifices. I used to wonder why Shinto religion does not have the custom

of animal sacrifices if Shinto originated from the religion of ancient

Israel.

But then I found the answer in Deuteronomy, chapter 12. Moses

commanded the people not to offer any animal sacrifices at any other locations

except at specific places in Canaan (12:10-14). Hence, if the Israelites came to

ancient Japan, they would not be permitted to offer animal

sacrifices.

Shinto shrine is usually build on a mountain or a hill.

Almost every mountain in Japan has a shrine, even you find a shrine on top of

Mt. Fuji. In ancient Israel, on mountains were usually located worship places

called "the high places". The temple of Jerusalem was built on a mountain (Mt.

Moriah). Moses was given the Ten Commandments from God on Mt. Sinai. It was

thought in Israel that mountain is a place close to God.

Many Shinto shrines

are built with the gates in the east and the Holy of Holies in the west as we

see in Matsuo grand shrine (Matuo-taisya) in Kyoto and others. While, others are

built with the gates in the south and the Holy of Holies in the north. The

reason of building with the gates in the east (and the Holy of Holies in the

west) is that the sun comes from the east. The ancient Israeli tabernacle or

temple was built with the gate in the east and the Holy of Holies in the west,

based on the belief that the glory of God comes from the east.

All Shinto shrines are made of wood. Many parts of the

ancient Israeli temple was also made of wood. The Israelites used stones in some

places, but walls, floors, ceilings and all of the insides were overlaid with

wood (1 Kings 6:9, 15-18), which was cedars from Lebanon (1 Kings 5:6). In Japan

they do not have cedars from Lebanon, so in Shinto shrines they use Hinoki

cypress which is hardly eaten by bugs like cedars from Lebanon.

The wood of

the ancient Israeli temple was all overlaid with gold (1 Kings 6:20-30). In

Japan the important parts of the main shrine of Ise-jingu, for instance, are

overlaid with gold.

When Japanese people pray in front of the Holy Place of a Shinto shrine, they firstly ring the golden bell which is hung at the center of the entrance. This was also the custom of the ancient Israel. The high priest Aaron put "bells of gold" on the hem of his robe. This was so that its sound might be heard and he might not die when ministered there (Exodus 28:33-35).

Golden bell at the entrance of Shinto shrine

Japanese people clap their hands two

times when they pray there. This was, in ancient Israel, the custom to mean, "I

keep promises." In the Scriptures, you can find the word which is translated

into "pledge." The original meaning of this word in Hebrew is, "clap his hand"

(Ezekiel 17:18, Proverbs 6:1). It seems that the ancient Israelites clapped

their hands when they pledged or did something important.

Japanese people

bow in front of the shrine before and after clapping their hands and praying.

They also perform a bow as a polite greeting when they meet each other. To bow

was also the custom of the ancient Israel. Jacob bowed when he was approaching

Esau (Genesis 33:3). Ordinarily, contemporary Jews do not bow. However, they

bow when reciting prayers. Modern Ethiopians have the custom of bowing, probably

because of the ancient Jews who emigrated to Ethiopia in ancient days. The

Ethiopian bow is similar to the Japanese bow.

We Japanese have the

custom to use salt for sanctification. People sometimes sow salt after an

offensive person leaves. When I was watching a TV drama from the times of the

Samurai, a woman threw salt on the place where a man she hated left. This custom

is the same as that of the ancient Israelites. After Abimelech captured an enemy

city, "he sowed it with salt" (Judges 9:45). We Japanese quickly interpret this

to mean to cleanse and sanctify the city.

I hear that when Jews move to a new house they sow it with salt to sanctify

it and cleanse it. This is true also in Japan. In Japanese-style restaurants,

they usually place salt near the entrance. Jews use salt for Kosher meat. All

Kosher meat is purified with salt and all meals start with bread and salt.

Japanese people place salt at the entrance

of a funeral home. After coming back from a funeral, one has to sprinkle salt on

oneself before entering his/her house. It is believed in Shinto that anyone who

went to a funeral or touched a dead body had become unclean. Again, this is the

same concept as was observed by the ancient Israelites.

Japanese "sumo" wrestler sowing

with salt

Japanese "sumo" wrestlers sow the

sumo ring with salt before they fight. European or American people wonder why

they sow salt. But Rabbi Tokayer wrote that Jews quickly understand its

meaning.

Japanese people offer salt every time they perform a religious

offering, This is the same custom used by the Israelites:"With all your

offerings you shall offer salt." (Leviticus 2:13)

Japanese people in old

times had the custom of putting some salt into their baby's first bath. The

ancient Israelites washed a newborn baby with water after rubbing the baby

softly with salt (Ezekiel 16:4). Sanctification and cleansing with salt and/or

water is a common custom among both the Japanese and the ancient

Israelites.

In the Hebrew Scriptures, the words "clean" and "unclean" often

appear. Europeans and Americans are not familiar with this concept, but the

Japanese understand it. A central concept of Shinto is to value cleanness and to

avoid uncleanness. This concept probably came from ancient Israel.

Buddhist temples have idols which are carved in

the shape of Buddha and other gods. However in Japanese Shinto shrines, there

are no idols.

In the center of the Holy of Holies of a Shinto shrine, there

is a mirror, sword, or pendant. Nevertheless, Shinto believers do not regard

these items as their gods. In Shinto, gods are thought to be invisible. The

mirror, sword, and pendant are not idols but merely objects to show that it is a

holy place where invisible gods come down.

In the ark of the covenant of

ancient Israel, there were stone tablets of God's Ten Commandments, a jar of

manna and the rod of Aaron. These were not idols, but objects to show that it

was the holy place where the invisible God comes down. The same thing can be

said concerning the objects in Japanese shrines.

Joseph Eidelberg, a Jew who once came

to Japan and remained for years at a Japanese Shinto shrine, wrote a book

entitled "The Japanese and the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel." He wrote that many

Japanese words originated from ancient Hebrew. For instance, we Japanese say

"hazukashime" to mean disgrace or humiliation. In Hebrew, it is "hadak hashem"

(tread down the name; see Job 40:12). The pronunciation and the meaning of both

of them are almost the same. We say "anta" to mean "you," which is the same

in Hebrew. Kings in ancient Japan were called with the word "mikoto," which

could be derived from a Hebrew word "malhuto" which means "his kingdom." The

Emperor of Japan is called "mikado." This resembles the Hebrew word, "migadol,"

which means "the noble." The ancient Japanese word for an area leader is

"agata-nushi;" "agata" is "area" and "nushi" is "leader." In Hebrew, they are

called "aguda"and "nasi."

When we Japanese count, "One, two, three... ten," we sometimes say: "Hi, fu,

mi, yo, itsu, mu, nana, ya, kokono, towo." This is a traditional expression,

but its meaning is unknown it is thought of as being Japanese.

It has been said that this expression

originates from an ancient Japanese Shinto myth. In the myth, the female god,

called "Amaterasu," who manages the world's sunlight, once hid herself in a

heavenly cave, and the world became dark. Then, according to the oldest book of

Japanese history, the priest called "Koyane" prayed with words before the cave

and in front of the other gods to have "Amaterasu" come out. Although the words

said in the prayer are not written, a legend says that these words were, "Hi,

fu, mi...."

"Amaterasu" is hiding in a

heavenly cave; "Koyane" is praying and "Uzume" is dancing.

Joseph Eidelberg stated that this is a beautiful Hebrew expression, if it is supposed that there were some pronunciation changes throughout history. These words are spelled: "Hifa mi yotsia ma na'ne ykakhena tavo."

This means: "The beautiful (Goddess).

Who will bring her out? What should we call out (in chorus) to entice her to

come?" This surprisingly fits the situation of the myth. Moreover, we

Japanese not only say, "Hi, hu, mi...," but also say with the same

meaning: "Hitotsu, futatsu, mittsu, yottsu, itsutsu, muttsu, nanatsu,

yattsu, kokonotsu, towo."

Here, "totsu" or "tsu" is put to each of "Hi,

hu, mi..." as the last part of the words. But the last "towo" (which means ten)

remains the same. "Totsu" could be the Hebrew word "tetse," which means, "She

comes out. " And "tsu" may be the Hebrew word "tse" which means "Come

out."

Eidelberg believed that these words were said by the gods who

surrounded the priest, "Koyane." That is, when "Koyane" first says, "Hi," the

surrounding gods add, "totsu" (She comes out) in reply, and secondly, when

"Koyane" says, "Fu," the gods add "totsu" (tatsu), and so on. In this way, it

became "Hitotsu, futatsu, mittsu...."

However, the last word, "towo," the

priest, "Koyane," and the surrounding gods said together. If this is the Hebrew

word "tavo," it means, "(She) shall come." When they say this, the female god,

"Amaterasu," came out.

"Hi, fu, mi..." and "Hitotsu, futatsu, mittsu..."

later were used as the words to count numbers.

In addition, the name of the

priest, "Koyane," sounds close to a Hebrew word, "kohen," which means, "a

priest." Eidelberg showed many other examples of Japanese words (several

thousand) which appeared to have a Hebrew origin. This does not appear to be

accidental.

In ancient Japanese folk songs, many words appear that are

not understandable as Japanese. Dr. Eiji Kawamorita considered that many of them

are Hebrew. A Japanese folk song in Kumamoto prefecture is sung, "Hallelujah,

haliya, haliya, tohse, Yahweh, Yahweh, yoitonnah...." This also sounds as if it

is Hebrew.

Similarity Between the Biblical Genealogy and Japanese Mythology

There is a remarkable similarity between the

Biblical article and Japanese mythology. A Japanese scholar points out that the

stories around Ninigi in the Japanese mythology greatly resemble the stories

around Jacob in the Bible.

In the Japanese mythology, the Imperial family of

Japan and the nation of Yamato (the Japanese) are descendants from Ninigi, who

came from heaven. Ninigi is the anscestor of the tribe of Yamato, or Japanese

nation. While Jacob is the anscestor of the Israelites.

In the Japanese

mythology, it was not Ninigi who was to come down from heaven, but the other.

But when the other was preparing, Ninigi was born and in a result, instead of

him, Ninigi came down from heaven and became the anscestor of the Japanese

nation. In the same way, according to the Bible, it was Esau, Jacob's elder

brother, who was to become God's nation but in a result, instead of Esau, God's

blessing for the nation was given to Jacob, and Jacob became the anscestor of

the Israelites.

And in the Japanese mythology, after Ninigi came from heaven,

he fell in love with a beautiful woman named Konohana-sakuya-hime and tried to

marry her. But her father asked him to marry not only her but also her elder

sister. However the elder sister was ugly and Ninigi gave her back to her

father. In the same way, according to the Bible, Jacob fell in love with

beautiful Rachal and tried to marry her (Genesis chapter 29). But her father

says to Jacob that he cannot give the younger sister before the elder, so he

asked Jacob to marry the elder sister (Leah) also. However the elder sister was

not so beautiful, Jacob disliked her. Thus, there is a parallelism between

Ninigi and Jacob.

And in the Japanese mythology, Ninigi and his wife

Konohana-sakuya-hime bear a child named Yamasachi-hiko. But Yamasachi-hiko is

bullied by his elder brother and has to go to the country of a sea god. There

Yamasachi-hiko gets a mystic power and troubles the elder brother by giving him

famine, but later forgives his sin. In the same way, according to the Bible,

Jacob and his wife Rachal bear a child named Joseph. But Joseph is bullied by

his elder brothers and had to go to Egypt. There Joseph became the prime

minister of Egypt and gets power, and when the elder brothers came to Egypt

because of famine, Joseph helped them and forgives their sin. Thus, there is a

parallelism between Yamasachi-hiko and Joseph.

Similarity between the biblical

genealogy and Japanese mythology

And in the Japanese mythology, Yamasachi-hiko

married a daughter of the sea god, and bore a child named Ugaya-fukiaezu.

Ugaya-fukiaezu had 4 sons. But his second and third sons were gone to other

places. The forth son is emperor Jinmu who conquers the land of Yamato. On this

line is the Imperial House of Japan.

While, what is it in the Bible? Joseph

married a daughter of a priest in Egypt, and bore Manasseh and Ephraim. Ephraim

resembles Ugaya-fukiaezu in the sense that Ephraim had 4 sons, but his second

and third sons were killed and died early (1 Chronicles 7:20-27), and a

descendant from the forth son was Joshua who conquered the land of Canaan (the

land of Israel). On the line of Ephraim is the Royal House of the Ten Tribes of

Israel.

Thus we find a remarkable similarity between the biblical genealogy

and Japanese mythology - between Ninigi and Jacob, Yamasachi-hiko and Joseph,

and the Imperial family of Japan and the tribe of Ephraim.

Furthermore, in

the Japanese mythology, the heaven is called Hara of Takama (Takama-ga-hara or

Takama-no-hara). Ninigi came from there and founded the Japanese nation.

Concerning this Hara of Takama, Zen'ichirou Oyabe, a Japanase researcher,

thought that this is the city Haran in the region of Togarmah where Jacob and

his anscestors once lived; Jacob lived in Haran of Togarmah for a while, then

came to Canaan and founded the Israeli nation.

Jacob once saw in a dream the

angels of God ascending and descending between the heaven and the earth (Genesis

28:12), when Jacob was given a promise of God that his descendants would inherit

the land of Canaan. This was different from Ninigi's descending from heaven, but

resembles it in image.

Thus, except for details, the outline of the Japanese

mythology greatly resembles the records of the Bible. It is possible to think

that the myths of Kojiki and Nihon-shoki, the Japanese chronicles written in the

8th century, were originally based on Biblical stories but later added with

various pagan elements. Even it might be possible to think that the Japanese

mythology was originally a kind of genealogy which showed that the Japanese are

descendants from Jacob, Joseph, and Ephraim.

The concept of uncleanness during menstruation and bearing child have existed in Japan since ancient times. It has been a custom in Japan since old days that woman during menstruation should not attend holy events at shrine. She could not have sex with her husband and had to shut herself up in a hut (called Gekkei-goya in Japanese), which is built for collaboration use in village, during her menstruation and several days or about 7 days after the menstruation. This custom had been widely seen in Japan until Meiji era (about 100 years ago). After the period of shutting herself up ends, she had to clean herself by natural water as river, spring, or sea. It there is no natural water, it can be done in bathtub. This resembles ancient Israeli custom very much. In ancient Israel, woman during menstruation could not attend holy events at the temple, had to be apart from her husband, and it was custom to shut herself up in a hut during her menstruation and 7 days after the menstruation (Leviticus 15:19, 28). This shutting herself up was said "to continue in the blood of her purification", and this was for purification and to make impurity apart from the house or the village.

Menstruation hut used by Falasha,

Ethiopian Jews

This remains true even today. There are no

sexual relations, for the days of menstruation and an additional 7 days. Then

the woman goes to the Mikveh, ritual bath. The water of the Mikveh must be

natural water. There are cases of gathering rainwater and putting it to the

Mikveh bathtub. In case of not having enough natural water, water from faucet is

added.

Modern people may feel irrational about this concept but women during

menstruation or bearing child need rest physically and mentally. Woman herself

says that she feels impure in her blood in the period. "To continue in the blood

of her purification" refers to this need of rest of her blood.

Not only

concerning menstruation, but also the concept concerning bearing child in

Japanese Shinto resembles the one of ancient Israel. A mother who bore a child

is regarded unclean in a certain period. This concept is weak among the Japanese

today, but was very common in old days. The old Shinto book, Engishiki (the 10th

century C.E.), set 7 days as a period that she cannot participate holy events

after she bore a child. This resembles an ancient custom of Israel, for the

Bible says that when a woman has conceived, and borne a male child, then she

shall be "unclean 7 days". She shall then "continue in the blood of her

purification 33 days". In the case that she bears a female child, then she shall

be "unclean two weeks", and she shall "continue in the blood of her purification

66 days'" (Leviticus 12:2-5).

In Japan it had been widely seen until Meiji

era that woman during pregnancy and after bearing child shut herself up in a hut

(called Ubu-goya in Japanese) and lived there. The period was usually during the

pregnancy and 30 days or so after she bore a child (The longest case was nearly

100 days). This resembles the custom of ancient Israel.

In ancient Israel,

after this period of purification the mother could come to the temple with her

child for the first time. Also in the custom of Japanese Shinto, after this

period of

purification the mother can come

to the shrine with her baby. In modern Japan it is generally 32 days (or 31

days) after she bore the baby in case of a male, and 33 days in case of a

female.

But when they come to the shrine, it is not the mother who carries

the baby. It is a traditional custom that the baby should be carried not by the

mother, but usually by the husband's mother (mother-in-law). This is a

remarkable similarity of purity and impurity of the mother, after childbirth,

with ancient Israeli custom.

Japanese "Mizura" and Jewish Peyot

The photo below (left) is a statue of an ancient Japanese Samurai found in relics of the late 5th century C.E. in Nara, Japan. This statue shows realistically the ancient Japanese men's hair style called "mizura," which hair comes down under his cap and hangs in front of both ears with some curling. This hair style was widely seen among Japanese Samurais, and it was unique to Japan, not the one which came from the cultures of China or Korea.

Ancient Japanese

Samurai's hair style "mizura" (left) and Jewish "peyot" (right)

Is it a mere coincidence that this resembles Jewish "peyot" very much, which is also a hair style of hanging the hair in front of the ears long with some curling (photo right)? "Peyot" is a unique hair style for Jews and the origin is very old. There is a statue from Syria, which is from the 8th or 9th century B.C.E.. It shows a Hebrew man with peyot and a fringed shawl.

The information on this page is only an introduction for my study. This page is chapter 1. Please click below for more information.

Chapter 2